BOOK EXCERPT:

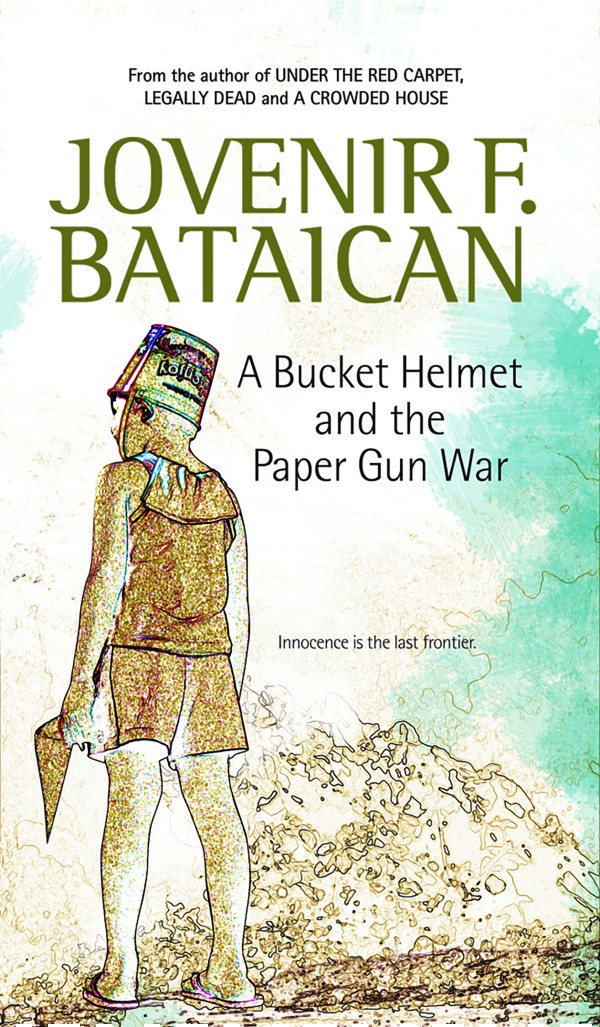

A Bucket Helmet and the Paper Gun War

Prologue: Take It On the Run.

IF HE COULD FLY, he would.

But his lungs were too close to bursting. His calloused feet had left behind the slippers he had been wearing. Now his feet hurt so badly, he knew he had cut either of them, or worse, both. The searing pain was not about to slow him down. His legs wished they had wings for their speed seemed never enough. His life depended on them now.

IT HAD STARTED like a regular weekend run. With the town’s rationed electricity out by midnight, the moon was the savior – out and bright – and he was hoping he could sell everything before sunrise. A few gas lamps that shone through windows from nearby homes belied the fact that everyone was still asleep. He’d known this neighborhood well. He realized he had passed by too early; he’d been too much in a hurry. It was still a quarter before four in the early morning. Ridiculously early especially on a weekend. He’d been told it was rude to rouse people up. Such was the nature of peddling the only community newspaper in town. Besides, it only happened on Saturdays.

His voice echoed in the empty streets, announcing the name of the weekend community newspaper he was peddling. He’d reached an intersection and thought about going inside a side street. He never had much luck there though. The main streets mattered. He took a breather. Then his eyes turned towards the roof of a single-story school building that was shrouded by the shadows of a cluster of tall trees less than a hundred feet away.

The creature, at first, had cleverly chosen to shroud itself behind these shadows. It was easy to miss. Somehow, he was inexplicably drawn to it. He thought he saw something move. He felt nailed to where he had stood.

Then the towering figure stepped out from behind the shadows. At first, he’d thought of the tricks the mind would play in an unholy hour like this. But the shadow seemed to step off that flat-roofed building. And floated. It was too big for a bird. Besides, birds didn’t hover; they’d fly away. That was definitely something else.

He dropped the newspaper bundle. As soon as it hit the ground, he let go a frantic wail. He took two tentative steps back, a quick turn, and off he ran like mad, leaving a trail of a terrified scream.

Ironic how he had always wished there were fewer boys like him selling those weekend papers. They had always argued amongst themselves which pair or group would get this street or that street. Even within the group, dividing the routes or streets and even alleys required a loud mix of haggling, pleading, even threatening. In the end, he’d gotten what he’d wanted with only another boy to compete with. The same boy he had tricked on leaving behind half an hour’s worth of headstart. Now, he was paying the price of mischief. He had no one close to ask help from.

THE LAST HE COULD REMEMBER was the shadow as it rose even higher not a few meters from where he had stood dumbstruck. He remembered screaming but no one had bothered to help. It really seemed that the whole place had conspired to play deaf to his pleas. Even the cool dawn air was menacingly still. He only had this debilitating fear and

confusion to power his desire to escape. He wasn’t even sure he was being chased. Why else would such a creature show itself if it had no plan of attacking? He didn’t intend to find out.

The only send-off he got came from a few dogs behind fences he passed by as he ran for his life. They were not barking either. Howling was the word. And if he believed all that he had heard about spooky shadows and howling dogs, he was quite sure both were inseparable.

It was more than a shadow or a figment of his imagination, that he was willing to bet. The creature was not only towering, it hovered. It had wings.

And all he could wish was that he had wings too as he kept on running.

Chapter 1: Morning Has Broken

I WAS EXCITED about Holy Week for the wrong reason. So obviously it wasn’t rooted on anything holy. Neither was I planning a lot of self sacrifice. Whatever deprivation we’d get during the Lenten season, most, if not everything were imposed on us: fasting, no merriments, no outdoor games, long and frequent prayers, no pork, and a lot of quiet time indoors meant for reflections but in reality were disguised forced naps. We couldn’t even hum or sing our favorite non-religious songs (which was fine with me because it spared me from my aunt’s merciless take on Barbra Streisand).

I shared the dread of Holy Week with just about all the kids my age and younger. It was the time when we’d get to be scared the most: Christ had died (again! and had apparently been betrayed by the same man; maybe being so forgiving had its downsides too) and He would not be able to protect us. Unlike Halloween when ghosts had a day or two of spooking mortals, our elders had warned us of an entire week of being vulnerable to “creatures of the dark,” never mind the fact that the summer of 1982 in Masbate was one of the hottest on record and the days were longer and the creatures of the dark had very little time to enjoy the dark itself.

This time, I had a very special reason to look forward to the Holy Week.

It was about the culmination of days of intense lobbying, haggling, convincing and even slight threatening for something I had sought for my own selfish want. As classes ended and summer started, it had also become a competition.

For reasons known only to Amanda, the girl I had been pursuing for four months now, she promised to tell me what her heart desired on Good Friday. To reveal such an important feeling on the day Christ was crucified was rather foreboding. But I was twelve years old then and I was quite sure, Christ was rather too preoccupied to mind my indiscretion. Amanda could be, if I got lucky, my very first girlfriend. Maybe she wasn’t even Catholic to begin with so Holy Week might not have been in her version of the Bible.

Yes, at twelve, I decided I wanted a girlfriend. And yes, I didn’t have a single idea what having one meant.

TWELVE WAS AN ODD AGE to be (even if twelve was an even number!) It’s the last year before I could even be declared a teen but somehow, finding a girlfriend became a race for me.

It wasn’t easy to be twelve. Not for someone who got uprooted again. Not with three other younger siblings to help look after. Not with an absentee father who was winning combats as an officer in the Army elsewhere but steadily losing the hearts of his family. And definitely not with a mother left on her own to take care of what her husband couldn’t. Or wouldn’t.

It wasn’t easy to be twelve – you’re neither young nor old. When it came to doing chores, “old enough” was invoked. But when it was time to ask for privileges, leniency and tolerance, you’d be too young. So when mother decided to pack our bags and leave Cebu for a place I and my siblings knew nothing about, my protests were ignored. Technically, I was a Masbateño. I was born here. But just weeks after being born, my parents –

Benjamin Almario, then a young lieutenant in the Army, and Eleonor Lorenzo-Almario, moved back to Cebu. Ten years later, for reasons only my mother and grandmother knew, we left the big city and returned.

I started as a quiet, awkward boy on my fifth grade in a public school we simply called North. The complete name was rather long (in honor of someone no one really bothered to explain why) and no kid could really remember it most days. Especially a big city boy student like me who almost didn’t pass and make it beyond Grade Two.

Apparently there was another school at the other end of the sleepy town known as South, and boy was the competition so fierce then as to which school was the best. In a faraway province like Masbate when what little ‘excitement’ was brought about by fraternity wars, political killings and sporadic clashes with rebels in the mountains, nervous residents would rather pit schools like the North and South as a much welcome alternative.

So it was that everyone rooted for his or her favorite school during Math, Science and English inter-school quizzes, or sports competitions. Never mind that there were other private schools in the fray. It was okay even for the North and the South to occasionally lose to these private schools. But the real battle was just between them. The funny thing was, when elementary school was over, both North and South would converge in the biggest public high school there and that petty competition was over and done with just like that!

So too during summer, when schools were out, it was back to fraternity wars, political killings and sporadic clashes with rebels in the mountains.

Relatives called me Lian. For those who knew that my full name was Alejandro, I ended up responding to Ale, Jan, Dro, Drew and even Andro, depending on how thick the accent of the speaker was. Just minutes after stepping into my environment: new classroom, new teacher, new classmates, my English teacher had already called my attention for being “talkative.” Quite an achievement really for someone who didn’t even understand nor speak the dialect yet.

This March, I graduated class valedictorian in a hotly contested race. There were protests raised against my being declared as such since I had only enrolled there on my fifth grade. There was a “residency” requirement that school officials had allegedly ignored. Honestly, I didn’t expect the honor as well and would have gladly relinquished it for those who badly wanted it. In that provincial capital, topping the heap in school was a source of bragging rights. I was a black horse who stole that pride from two top contenders whose families seemed to own the rights to such honors.

In their eyes, I had not only “stolen” the honor, I had also trampled on their egos and worse, family honor. One of those contenders was Marlon. Up until the fifth grade, he was the top student in class. How he’d ended up as third in the final ranking when we reached Grade Six was a mystery I had no interest to solve. He even missed graduation. Rumors had it he was badly beaten by his father, he had to stay home with his bruises.

At twelve, guilt was hardly felt even for mischiefs I had done. How much more for something I believed wasn’t my own doing.

In fact, I couldn’t care less if half the graduating class missed the ceremonies. That would have drastically shortened the waiting time just sitting and sweating it out in a suffocating toga under the mid-morning summer sun. I would have skipped the suffering myself if not for mother insisting that I should be there since I “topped the batch.” It was a phrase that meant nothing to me. All our young lives, we had been taught that we had to study hard to better our selves and prepare for the future. No one had said about competing with anyone. Certainly not against a “batch.” Graduation meant only one thing: school was over. That was reward enough for me.

THEN CAME THE SUMMER of 1982. To my mind, it seemed like yesterday. The memories were as vivid as when these had actually happened.

Urgency was alien and pessimism was fast becoming an antidote for hopefulness. In a place distinguished for its people’s sighs, a scream was, for the best part, a sign that there still remained a much stronger expression other than apathy and quiet indifference.

So it started with a scream. And I, at twelve, was even more convinced that I was about to live through a most unforgettable chapter in my life.

FATHER WAS NOW A CAPTAIN in the Army at a time when soldiers had the most powerful uniform in the country. Martial Law technically ended a year ago, but nothing had changed. Men like him still brandished power and influence like demigods. At first the thought made me proud. People, especially from where I came from, seemed to speak about my father in hushed – almost reverent – tones. I never really figured out at that time that the difference between being revered and despised was simply lost in the whispers.

He was most loved, even sought after, when he was sober. When drunk, he was a totally different person. Mother would later admit that his drinking transformed him from a person to a monster of some kind. It didn’t help that he was a soldier and that he had guns being kept in the house. In several drunken episodes back when we were still in Cebu City, he would discharge a firearm – aimed at the ceiling – within feet from us, his children. Those were scary moments. Neighbors would call in the cops and they’d encircle the house with their megaphones. We would cower in fear but father would sober up just like that and settle the furor by himself. Soon, the cops became his friends and those shooting incidents seemed to be an excuse to gather and drink some more.

We never had an idea how these episodes had emotionally scarred our mother. She kept her pains to herself, maybe because she knew we’d been too young then to understand.

Still, as the supposedly head of the family, we saw less and less of our father the past years. He was always on assignment in some distant parts of the country and mother thought it would be unwise, even dangerous for us to tag along. Whenever I would start missing him, I would just try to remember what he was when drunk and somehow, I’d be okay he was away.

He did come with us on the boat ride from Cebu to Masbate that summer of 1980. Like a “dutiful” soldier, he paraded his full battle gear even in the company of his family. He had a few beers and mother was worried all throughout the eighteen-hour boat trip that he would pull his OK Corral act in mid-sea. There would be no cops to surround him and there was no way of knowing how the other passengers would react. But father somehow

knew he had to behave.

One of my most enduring memories of him was when the boat had docked but we couldn’t seem to get down the gangplank because the porters and other passengers refused to give way. The few security guards from the shipping company were helpless as the incoming passengers started boarding the boat without allowing the arriving ones to disembark first.

“Doesn’t that worry you,” my younger sister Gwen whispered, “that they seem to be in a hurry to leave the place?” I offered no answer. I did silently wish they wouldn’t let us leave the boat so we could just ride it back to Cebu.

Father, who had been drinking the previous night and was still nursing a hangover, had pretended to have patience for a time before brandishing his Armalite rifle with an attached M203 (a grenade launcher) and threatening to shoot anyone who got in the way. Suddenly, we had the gangplank all to ourselves.

That was the peak of my conceit for having a father with “power”.

He’d only stayed with us for a couple of days after ‘delivering’ us here. In the year that followed, he only visited us once. It was a strange visit one morning in September 1981. He’d told mother his unit just dropped a wounded comrade in the military hospital here. He then spent the night visiting friends. Mother had said she met our father in Masbate where he had trained after enlisting and he had befriended many in this town. It was her way of saying we shouldn’t expect much from such visits.

Our excitement for having him around gave way to disappointment. I had always believed we should have meant more to him than his friends.

I didn’t see him until he dropped by to say goodbye three days later.